| Component | Choice |

|---|---|

| Interpreter/Language | R, Python, JavaScript |

| IDE/Editor | R Studio, VS Code, Sublime |

| Version Control | Git |

| Project Management | GitHub, GitLab |

| database | PostgreSQL |

| "Virtual" Environments | Docker |

| Communication (Visualization, Web) | Node, Quasar (vue.js) |

| Website Hosting | Netlify, GitHub Pages |

| Workflow automation | Apache Airflow |

| Continous Integration | Woodpecker, GitLab CI, GitHub Actions |

2 Stack: A Developer’s Toolkit

The goal of this chapter (and probably the most important goal of this entire book) is to help you see the big picture of which tool does what. The following sections will group common programming-with-data components by purpose. All of the resulting groups represent aspects of programming with data, and I will move on to discuss these groups in a dedicated chapter each.

Just like natural craftsmen, digital carpenters depend on their toolbox and their mastery of it. A project’s stack is what developers call the choice of tools used in a project. Even though different flavors come down to personal preferences, there is a lot of common ground in programming with data stacks. Table 2.1 shows some of the components I use most often grouped by their role. Of course, this is a personal choice. Obviously, I do not use all of these components in every single small project. Git, R and R Studio would be a good minimal version.

Throughout this book, often a choice for one piece of software needs to be made to illustrate things. To get the most out of the book, keep in mind that these choices are examples and try to focus on the role of an item in the big picture.

2.1 Programming Language

In Statistical Computing, the interface between the researcher and the computation node is almost always an interpreted programming language as opposed to a compiled one. Compiled languages like C++ require the developer to write source code and compile, i.e., translate source code into what a machine can work with before runtime. The result of the compilation process is a binary which is specific to an operating system. Hence, you will need one version for Windows, one for OSX and one for Linux if you intend to reach a truly broad audience with your program. The main advantage of a compiled language is speed in terms of computing performance, because the translation into machine language does not happen during runtime. A reduction of development speed and increase in required developer skills are the downside of using compiled languages.

Big data is like teenage sex: everyone talks about it, nobody really knows how to do it, everyone thinks everyone else is doing it, so everyone claims they are doing it. – Dan Ariely, Professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics on X1

The above quote became famous in the hacking data community, not only because of the provocative, fun part of it, but also because of the implicit advice behind it. Given the enormous gain in computing power in recent decades, and also methodological advances, interpreted languages are often fast enough for many social science problems. And even if it turns out, your data grow out of your setup, a well-written proof of concept written in an interpreted language can be a formidable blueprint. Source code is turning into an important scientific communication channel. Put your money on it, your interdisciplinary collaborator from the High Performance Computing (HPC) group will prefer some Python code as a briefing for their C++ or Fortran program over a wordy description out of your field’s ivory tower.

Interpreted languages are a bit like pocket calculators, you can look at intermediate results, line-by-line. R and Python are the most popular open source software (OSS) choices for hacking with data, Julia (Bezanson et al. 2017) is an up-and-coming, performance-focused language with a much slimmer ecosystem. A bit of JavaScript can’t hurt for advanced customization of graphics and online communication of your results.

2.2 Interaction Environment

While the fact that a software developer needs to choose a programming language to work with is rather obvious, the need to compose and customize an environment to interact with the computer is much less obvious to many. Understandably so because, outside of programming, software such as word processors, video or image editors presents itself to the user as a single program. That single program takes the user’s input, processes the input (in memory) and stores a result on disk for persistence – often in a proprietary, program specific format.

Yet, despite all the understanding for nonchalantly saying we keep documents in Word or data in R Studio, it’s beyond nerdy nitpicking when I insist that data are kept in files (or databases) – not in a program. And that R is not R Studio: This sloppy terminology contributes to making us implicitly accept that our office documents live in one single program. (And that there is only one way to find and edit these files: through said program).

It is important to understand that source code of essentially any programming languages is a just a plain text file and therefore can be edited in any editor. Editors come in all shades of gray: from lean, minimal code highlighting support to full-fledged integrated development environments (IDEs) with everything from version control integration to sophisticated debugging.

Which way of interaction the developer likes better is partly a matter of personal taste, but it also depends on the programming language, the team’s form of collaboration and size of the project. In addition to a customized editor, most developers use some form of a console to communicate with their operating system. The ability to send commands instead of clicking is not only reproducible and shareable, but it also outpaces mouse movement by a lot when commands come in batches. Admittedly, configuration, practice and getting up to speed takes time, but once you have properly customized the way you interact with your computer when writing code, you will never look back.

In any case, make sure to customize your development environment: choose the themes you like, make sure the cockpit you spent your day in is configured properly and feels comfy.

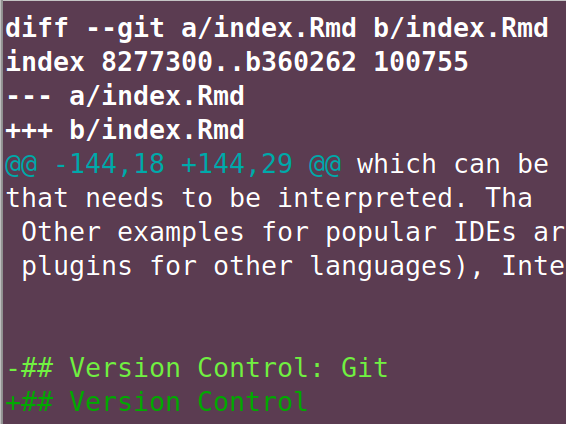

2.3 Version Control

To buy into the importance of managing one’s code professionally may be the single most important take-away from this book. Being able to work with will help you fit into numerous different teams that have contact points with data science and programming, let alone if you become part of a programming or data science team.

While has a long history dating back to CVS2 and SVN3, the good news for the learner is, that there is a single dominant approach when it comes to in the data analysis world. Despite the fact that its predecessors and alternatives such as Mercurial are still around, git4 is the one you have to learn. To learn more about the history of and approaches other than git, Eric Sink’s Version Control by Example (Sink 2011) is for you.

So what does git do for us as researchers? How is it different from Dropbox?

git does not work like dropbox. git is not like dropbox.

git does not work like dropbox. git is not like dropbox.

git does not work like dropbox. git is not like dropbox.

git does not work like dropbox. git is not like dropbox.

git does not work like dropbox. git is not like dropbox.

git does not work like dropbox. git is not like dropbox.

The idea of thinking of a sync is what interferes with comprehension of the benefit of (which is why I hate that git GUIs call it “sync” anyway to avoid irritation of user’s initial beliefs.). Git is a decentralized system that keeps track of a history of semantic commits. Those commits may consist of changes to multiple files. A commit message summarizes the gist of a contribution. Diffs allow comparing different versions.

Git is well suited for any kind of text file, whether it is source code from Python or C++, or some text written in Markdown or LaTeX. Binaries like .pdfs or Word documents are possible, too, but certainly not the type of file for which git is really useful. This book contains a detailed, applied introduction tailored to researchers in a dedicated chapter, so let’s dwell with the above contextualization for a bit.

2.4 Data Management

One implication of bigger datasets and/or bigger teams is the need to manage data. Particularly when projects establish themselves or update their data regularly, well-defined processes, consistent storage and possibly access management become relevant. But even if you worked alone, it can be very helpful to have an idea about data storage in files systems, memory consumption and archiving data for good.

Data come in various forms and dimensions, potentially deeply nested. Yet, researchers and analysts are mostly trained to work with one-row-one-observation formats, in which columns typically represent different variables. In other words, two-dimensional representation of data remains the most common and intuitive form of data to many. Hence, office software offers different, text-based and proprietary spreadsheet file formats. On disk, comma separated files (.csv)5 are probably the purest representation of two-dimensional data that can be processed comfortably by any programming language and that can be read by many programs. Other formats such as .xml or .json allow storing even deeply nested data.

In-memory, that is when working interactively with programming languages such as R or Python, data.frames are the most common representation of two-dimensional data. Data.frames, their progressive relatives like tibbles or data.tables and the ability to manipulate them in reproducible, shareable and discussible fashion is the first superpower upgrade over pushing spreadsheets. Plus, other representation such as arrays, dictionaries or lists represent nested data in memory. Though in-memory data manipulation is very appealing, memory is limited and needs to be managed. Making the most of the memory available is one of the driving forces behind extensions of the original data.frame concept.

The other obvious limitation of data in memory is the lack of persistent storage. Therefore, in-memory data processing needs to be combined with file based storage are a database. The good news is that languages like R and Python are well-equipped to interface with a plethora of file-based approaches as well as databases. So well, that I often recommend these languages to researchers who work with other less-equipped tools, solely as an intermediate layer.

To evaluate which relational (essentially SQL) or non-relational database to pick up just seems like the next daunting task of stack choice. Luckily, in research, first encounters with a database are usually passive, in the sense that you want to query data from a source. In other words, the choice has been made for you. So unless you want to start your own data collection from scratch, simply sit back, relax and let the internet battle out another conceptual war. For now, let’s just be aware of the fact that a data management game plan should be part of any analysis project.

2.5 Infrastructure

For researchers and business analysts who want to program with data, the starting infrastructure is very likely their own desktop or notebook computer. Nowadays, this already means access to remarkable computing power suited for many tasks.

Yet, it is good to be aware of the many reasons that can turn the infrastructure choice from a no-brainer into a question with many options and consequences. Computing power, repeated or scheduled tasks, hard-to-configure or non-compatible runtime environment, online publication or high availability may be some of the needs that make you think about infrastructure beyond your own notebook.

Today, thanks to software-as-a-service (SaaS) offers and cloud computing, none of the above needs imply running a server, let alone a computing center on your own. Computing has not only become more powerful over the last decade, but also more accessible. Entry hurdles are lower than ever. Many needs are covered by services that do not require serious upfront investment. It has become convenient to try and let the infrastructure grow with the project.

From a researcher’s and analyst’s perspective, one of the most noteworthy infrastructure developments of recentness may be the arrival of containers in data analysis. Containers are isolated, single-purpose environments that run either on a single container host or with an orchestrator in a cluster. Although technically different from virtual machines, we can regard containers as virtual computers running on a computer for now. With containers, data analysts can create isolated, single purpose environments that allow to reproduce analysis even after one’s system was upgraded and with it all the libraries used to run the analysis. Or think of some exotic LaTeX configuration, Python environment or database drivers that you just can’t manage to run on your local machine. Bet there is a container blueprint (aka image) around online for exactly this purpose.

Premature optimization is the root of all evil. – Donald Knuth.

On the flip side, product offerings and therefore our options have become a fast-growing, evolving digital jungle. So, rather than trying to keep track (and eventually loosing it) of the very latest gadgets, this book intends to show a big picture{big picture} overview and pass on a strategy to evaluate the need to add to your infrastructure. Computing power, availability, specific services and collaboration are the main drivers for researchers to look beyond their own hardware. Plus, public exposure, i.e., running a website as discussed in the publishing section, asks for a web host beyond our local notebooks.

2.6 Automation

“Make repetitive work fun again!” could be the claim of this section. Yet, it’s not just the typical intern’s or student assistant’s job that we would love to automate. Regular ingestion of data from an application programming interface (API) or a web scraping process are one form of reoccurring tasks, often called cron jobs after the Linux cron command, which is used to schedule execution of Linux commands. Regular computation of an index, triggered by incoming data would be a less time-focused, but more event-triggered example of an automated task.

The one trending form of automation, though, is continuous integration/continuous development (CI/CD). CI/CD processes are typically closely linked to a git repository and are triggered by a particular action done to the repository. For example, in case some pre-defined part (branch) of a git repository gets updated, an event is triggered and some process starts to run on some machine (usually some container). Builds of software packages are very common use cases of such a CI/CD process. Imagine you are developing an R package and want to run all the tests you’ve written, create the documentation and test whether the package can be installed. Once you’ve made your changes and push to your remote git repository, your push triggers the tests, the check, the documentation rendering and the installation. Potentially a push to the main branch of your repository could even deploy a package that cleared all of the above to your production server.

Rendering documentation, e.g., from Markdown to HTML into a website or presentation or a book like this one is a very similar example of a CI/CD process. Major git providers like Gitlab (GitLab CI/CD) or GiTHub (GitHub Actions) offer CI/CD tool integration. In addition, standalone services like CircleCI can be used as well as open source, self-hosted software like Woodpecker CI6.

2.7 Communication Tools

Its community is one of the reasons for the rise of open source software over the last decades. Particularly, newcomers would miss a great chance for a kick-start into programming if they did not connect with the community. Admittedly, not all the community’s communication habits are for everyone, yet it is important to make your choices and pick up a few channels.

Chat clients like Slack, Discord or the Internet Relay Chat (IRC) (for the pre-millenials among readers) are the most direct form of asynchronous communication. Though many of the modern alternatives are not open source themselves, they offer free options and remain popular in the community despite self-hosted approaches such as matrix7 along with Element8. Many international groups around data science and statistical computing such as RLadies or the Society of Research Software Engineering have Slack spaces that are busy 24/7 around the world.

Social media is less directed and more easily consumed in a passive fashion than a chat space. Over the last decade, X, formerly known as twitter, has been a very active and reliable resource for good reads but has seen parts of the community switch to more independent platforms such as Mastodon9. Linkedin is another suitable option to connect and find input, particularly in parts of the world where other platforms are less popular. Due to its activity, social media is also a great way to stay up-to-date with the latest developments.

Mailing lists are another, more old-fashioned form to discuss things. They do not require a special client and just an e-mail address to subscribe to their regular updates. If you intend to avoid social media, as well as signing up at knowledge sharing platforms such as stackoverflow.com10 or reddit11, mailing lists are a good way to get help from experienced developers.

Issue trackers are one form of communication that is often underestimated by newcomers. Remotely hosted git repositories, e.g., repositories hosted at GitHub or GitLab, typically come with an integrated issue trackers to report bugs. The community discusses a lot more than problems on issue trackers: feature requests are a common use case, and even the future direction of an open source project may be affected substantially by discussions in its issue tracker.

2.8 Publishing and Reporting

Data analysis hopefully yields results that the analyst intends to report internally within their organization or share with the broader public. This has led to a plethora of options on the reporting end. Actually, data visualization and reproducible, automated reporting are two of the main drivers researchers and analysts turn to programming for their data analysis.

In general, we can distinguish between two forms of output: pdf-like, print-oriented output and HTML-centered web content. Recent tool chains have enabled analysts without strong backgrounds in web frontend development (HTML/CSS/JavaScript) to create nifty reports and impressive, interactive visualizations. Frameworks like R Shiny or Python Dash even allow creating complex interactive websites.

Notebooks that came out of the Python world established themselves in many other languages implementing the idea of combining text with code chunks that get executed when the text is rendered to HTML or PDF. This allows researchers to describe, annotate and discuss results while sharing the code that produced the results described. In academia, progressive scholars and journals embrace this form of creating manuscripts as reproducible research that improves trust in the presented findings.

Besides academic journals that started to require researchers to hand in their results in reproducible fashion, reporting based on so-called static website generators12 has taken data blogs and reporting outlets including presentations by storm. Platforms like GitHub render Markdown files to HTML automatically, displaying formatted plain text as a decent website. Services such as Netlify allow using a broad variety of build tools to render input that contains text and code.

Centered around web browsers to display the output, HTML reporting allows creating simple reports, blogs, entire books (like this one) or presentation slides for talks. But thanks to document converters like Pandoc and a typesetting juggernaut called LaTeX, rendering sophisticated .pdf is possible, too. Some environments even allow rendering to proprietary word processor formats.

https://x.com/danariely/status/287952257926971392↩︎

Concurrent Versions System: https://cvs.nongnu.org/↩︎

Apache Subversion↩︎

https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Getting-Started-About-Version-Control↩︎

Some dialects use different separators like ‘;’ or tabs, partly because of regional differences like the use of commas as decimal delimiters.↩︎

https://woodpecker-ci.org/↩︎

https://matrix.org/↩︎

https://element.io/↩︎

https://mastodon.social/↩︎

https://stackoverflow.com↩︎

https://reddit.com↩︎

As opposed to content management systems (CMS) that keep content in a database and put content and layout template together when users visit a website, static website generators render a website once triggered by an event. If users want to update a static website, they simply rerun the render process and push the HTML output of said process online.↩︎